Vitess has an opinionated approach to database scalability. Some of those opinions have minimal controversy such as how durability should be provided via replication, but the one I find interesting is the 250GB per MySQL server recommendation.

Is this a physical MySQL Limit? #

In short: no. By “physical limit” I mean is there a file format restriction that says databases can not be greater than 250GB?

The physical limit for InnoDB is 64TB per tablespace, and in the default configuration each table is its own tablespace. With table partitioning, this limit can be extended even further.

Is this a practical MySQL Limit? #

In short: not necessarily. By “practical limit”, I mean does MySQL instantly break down when it hits 250GB in database size? It is not uncommon for practical limits to be reached before physical limits.

The answer to this depends a lot on the table structure (and query patterns). Take these scenarios for example:

Table A:

CREATE TABLE tablea (

id INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY auto_increment,

b DATETIME NOT NULL,

c VARBINARY(512) NOT NULL,

INDEX(b)

);

Table B:

CREATE TABLE tableb (

id INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY auto_increment,

b DATETIME NOT NULL,

c VARBINARY(512) NOT NULL,

UNIQUE (c)

);

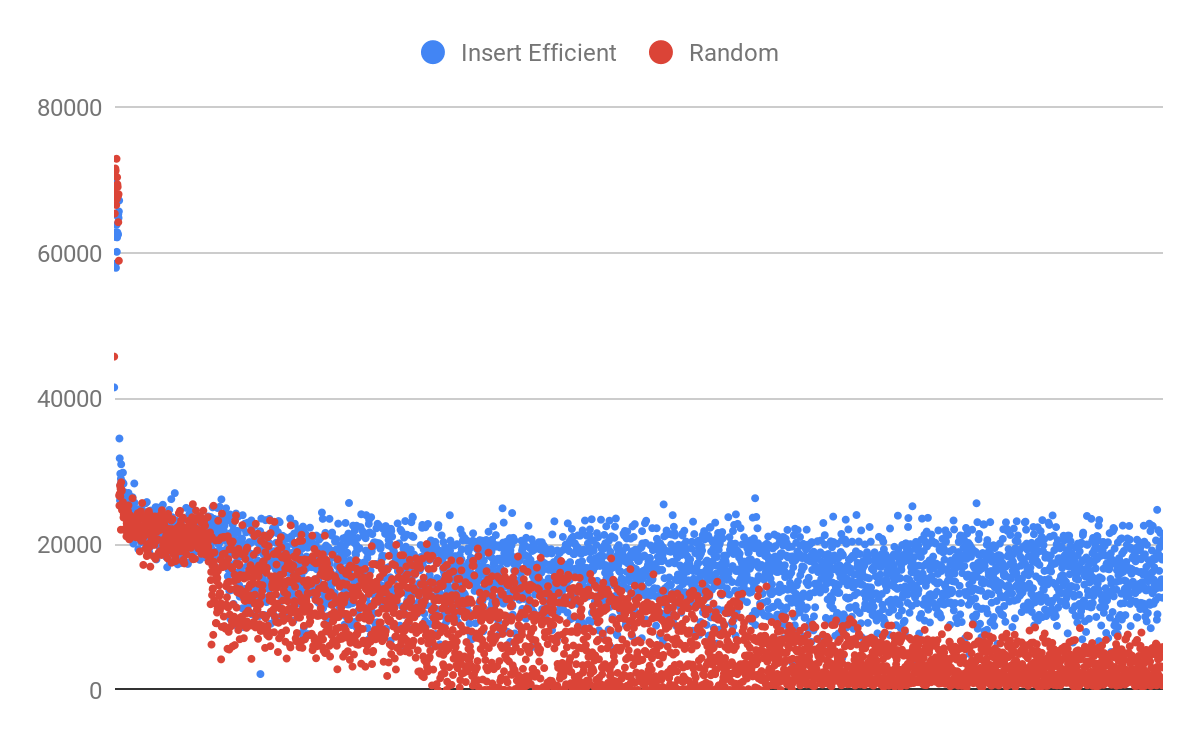

.. they look almost identical right? Lets try and insert rows into them in 32 parallel threads for one hour:

INSERT INTO {tablename} (b, c) VALUES (NOW(), RANDOM_BYTES(512)), (NOW(), RANDOM_BYTES(512)), ..;

Why do these two tables perform so wildly different? #

The index on c is wider (512 bytes vs. 6 bytes), but the random insertion combined with uniqueness is the real performance killer over time.

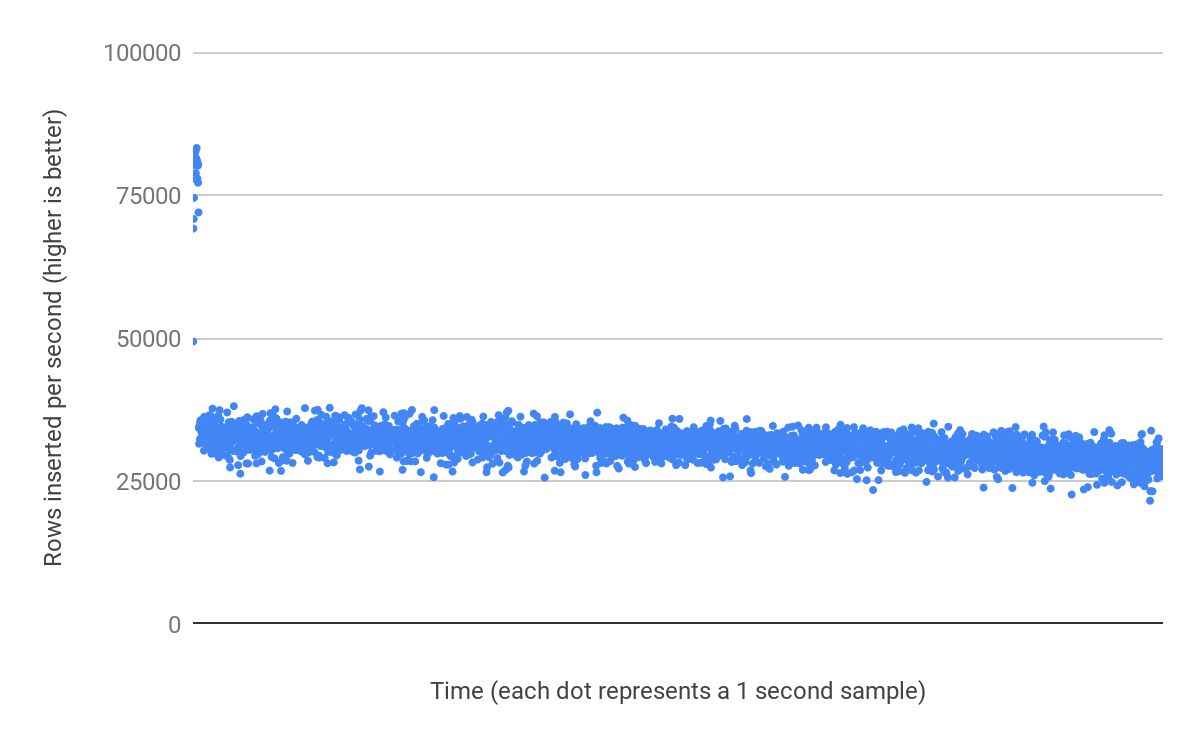

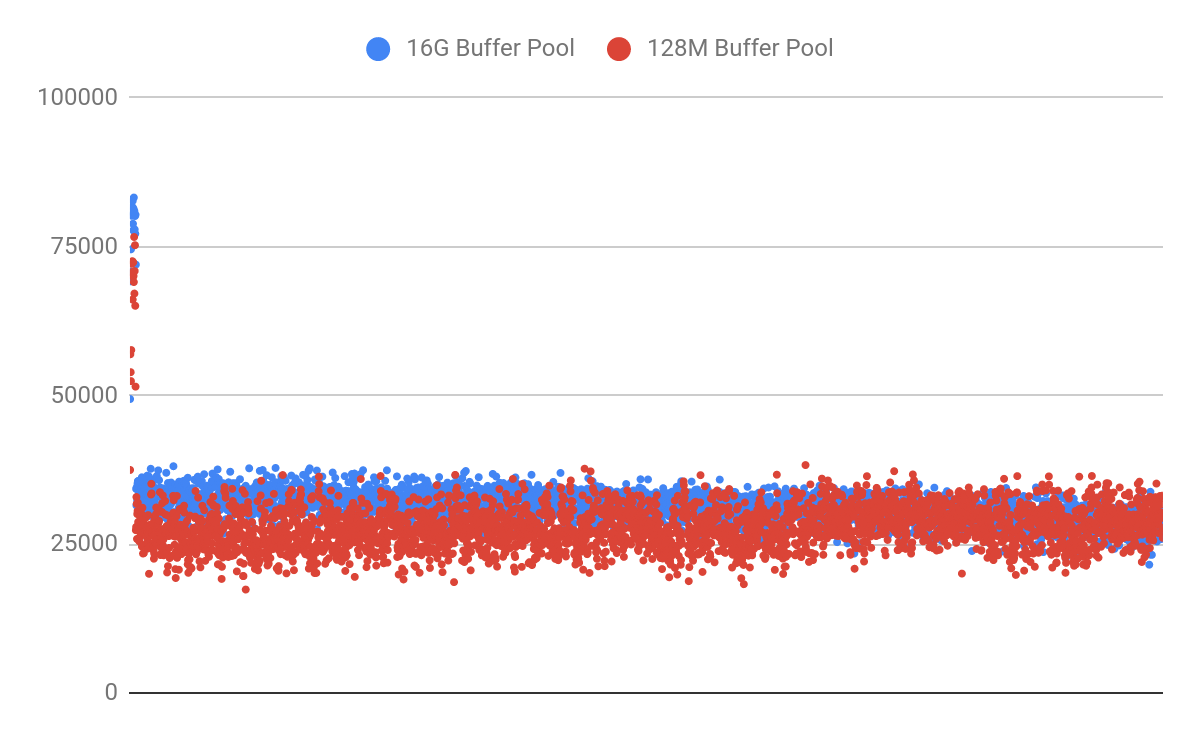

With Table A, the performance is stable and consistent because the inserts are to the end of the table and the required pages are in memory. I repeated the benchmark with a 128MB buffer pool and observed only a 13% decrease in performance:

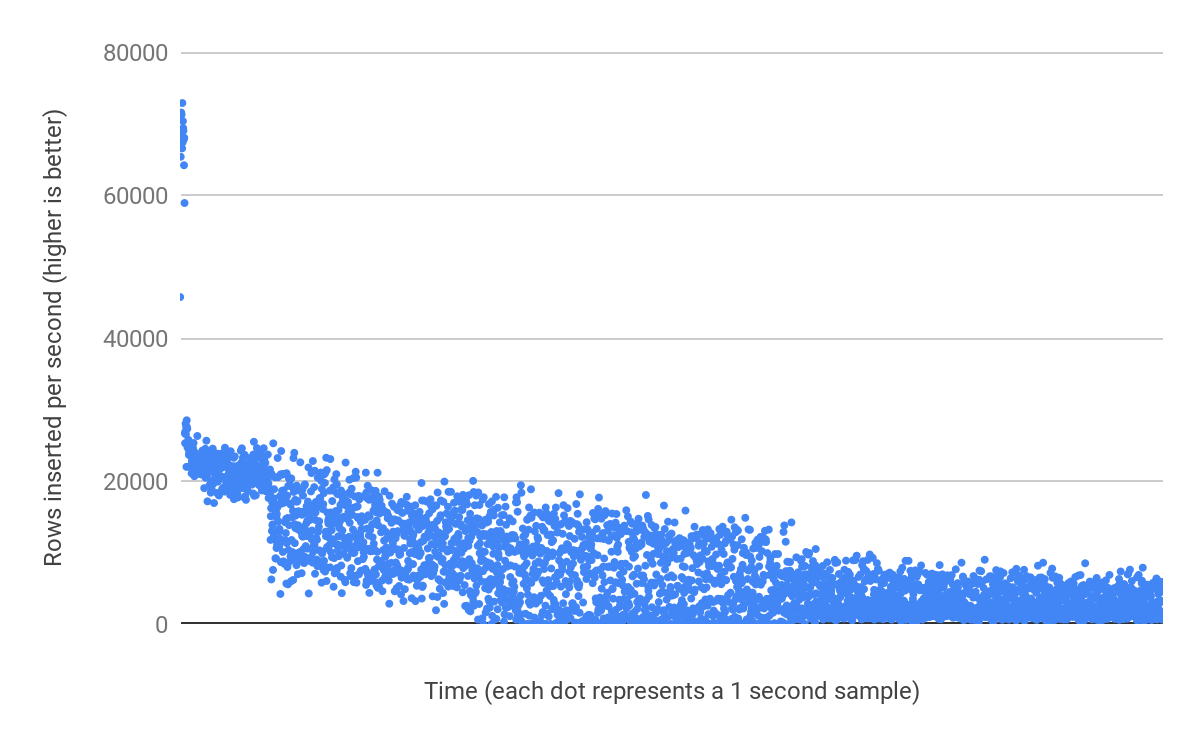

With Table B, insert performance is not sustained during the run time of the benchmark. Because the insert pattern on the unique index is random, there is no guarantee that the required index pages are in memory. But those pages must be loaded to make sure that a constraint check is not violated (column c must be unique).

So it is fair to say that the workload on Table B requires a higher memory fit than the workload on Table A. We could also improve performance by switching from RANDOM_BYTES(512) to something that is more insert efficient but still 512 bytes:

SELECT LENGTH(CONCAT(current_timestamp(6), RANDOM_BYTES(486)));

+---------------------------------------------------------+

| LENGTH(CONCAT(current_timestamp(6), RANDOM_BYTES(486))) |

+---------------------------------------------------------+

| 512 |

+---------------------------------------------------------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

Converting to Insert Efficient #

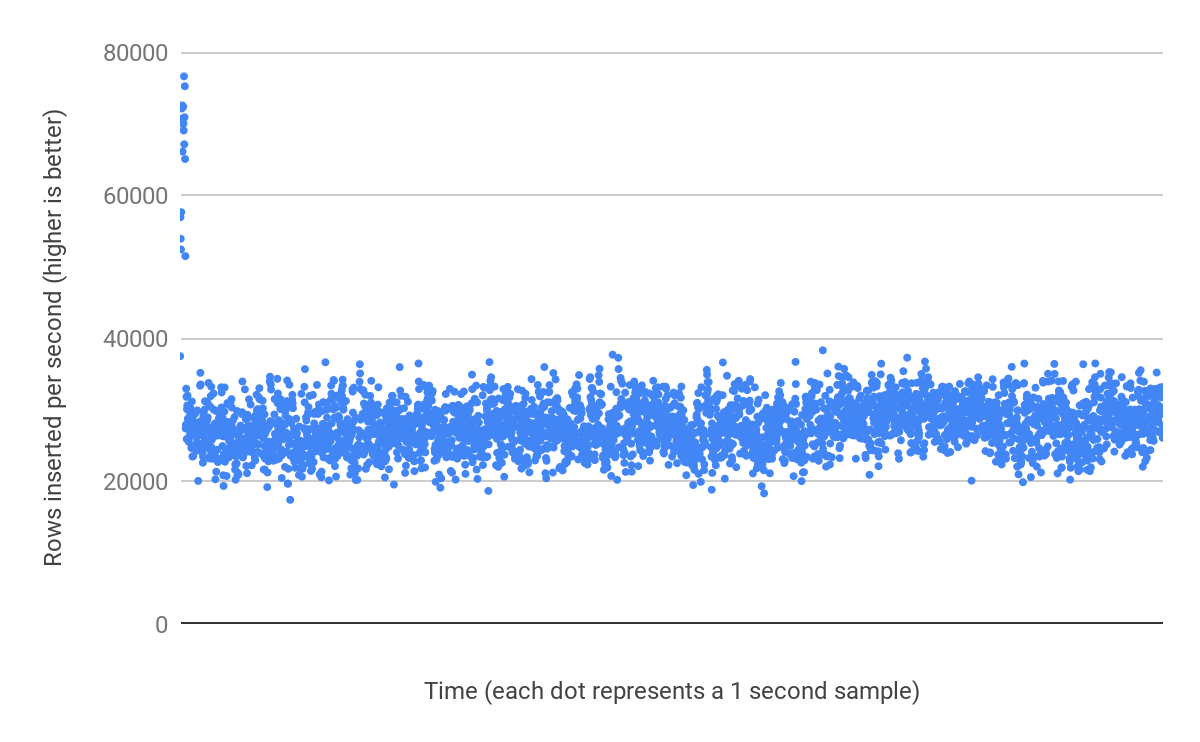

By prepending the random bytes with 26 bytes of a timestamp, the value becomes insert efficient. With our 16GB buffer pool we now have a very low rate of read-modify-write and can sustain performance as the table grows.

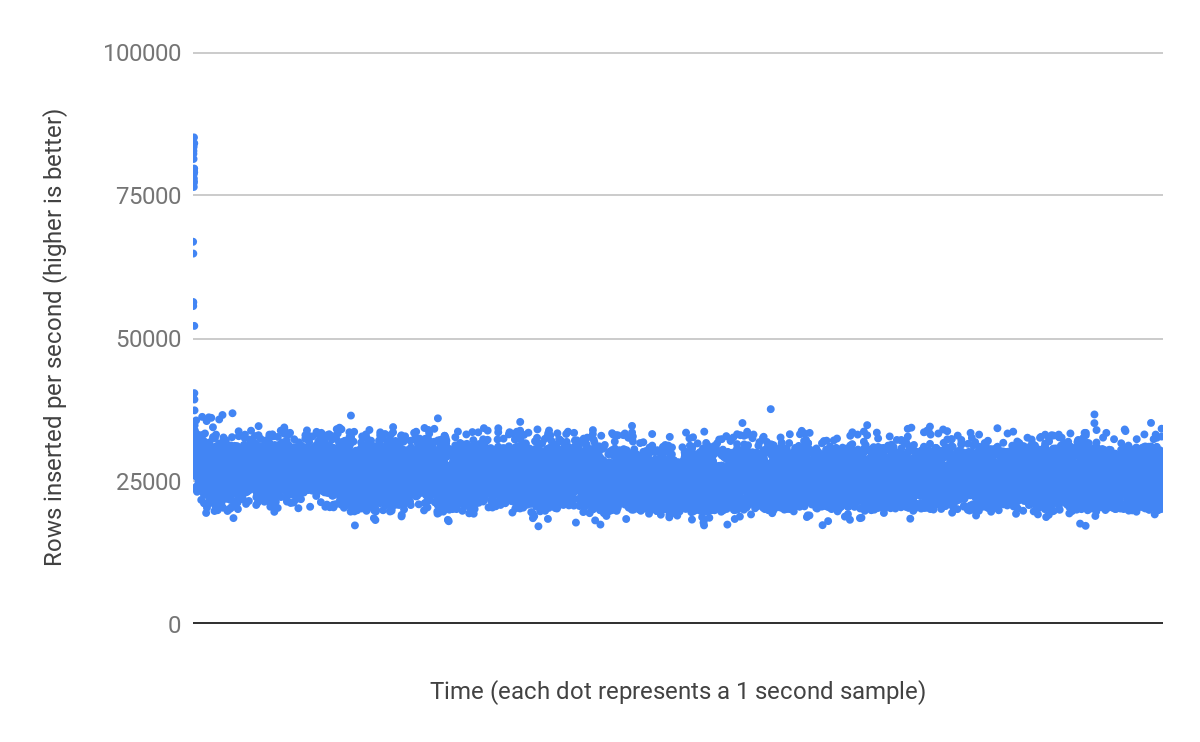

How far can an efficient inserts scale? #

Table A only lost 13% of its insert performance when the buffer pool was lowered from 16GB to 128MB. To prove that there is not a clear “maximum number of rows” limit, let’s now extend the test run time to 5 hours. After inserting almost 463 million rows, we can see our 376GB table still retains most of its insert performance:

Insert performance is not limited by data size, or number of rows. It is dependent on the table+index structure, and how rows are inserted. It is really difficult to provide a generalized answer here. You could have a 256GB database that works well with 1GB RAM, and another 256GB database that requires 128GB RAM.

Okay, why the limit? #

The example in the previous section described insert performance to illustrate a point. But performance is not limited to insert performance :-) Specifically, some management tasks become more difficult with larger databases:

- Taking a full backup

- Provisioning a new read replica

- Restoring a backup

- Making a schema change

- Reducing replica delay

Let’s use a 4TB shard failure as an example:

- When the master fails, the blast radius will be much larger, potentially taking more of the service offline.

- When a replica fails, it will likely take 10-12 hours to restore a new replica at gigabit network speed. While this time can be reduced with a higher speed network (recommended); there is a fairly large window for a secondary failure could occur. Many Vitess users aim for 15 minute recoveries; which is possible with a 250G shard on a 2.5Gbps network.

Vitess does not impose 250GB as a hard limit. It even encourages you to run multiple instances of MySQL (multiple tablets) on the same host.

Conclusion #

By specifying a recommended size, the authors of Vitess can also make assumptions about how long certain operations should take and simplify the design of the system. Or to paraphrase: the Vitess authors decided against a one-size-fits-all approach to scalability, and looping back to my opening sentence: Vitess has an opinionated approach to scalability.

TL;DR: Vitess suggests 250G as a shard size for management and predictable recovery times. It may be true for performance reasons too, but that depends a lot on your usage.

Test Disclosure #

- 8 Core (16 thread) Ryzen 1700

- 64GiB RAM (MySQL intentionally limited with O_DIRECT)

- Samsung EVO 970 1TB

- Ubuntu 19.04

- MySQL 8.0.17

- MySQL Config:

- innodb-buffer-pool-size= 16G (modified to 128M in second Table A test)

- innodb-flush-method=O_DIRECT

- innodb-log-file-size=4G

- innodb-io-capacity=2000

- innodb-io-capacity-max=5000

- binlog_expire_logs_seconds=30

- skip-mysqlx

- max-binlog-size=100M

- Benchmark inserts in 32 threads (gist)